Professor Jacques El-Hakim: The Leading Authority On Syrian Law

The year is 1956 and while Syrians have successfully reinstalled their scion of the independence movement Shukri Quwatli for a second stint as president a year earlier, nobody can deny that the Army’s power is slowly on the rise once again. One of the consequences of the growing authority of the military is on display in a Damascus courtroom. The defendant is a colonel in the Syrian Army accused of bribery and embezzlement of public funds. Although the courts are trying to keep a check on the sway of Army officers, the case against the Colonel is testament to the ascendancy of the military in the country.

As the presiding Judge gets ready to declare the court in session, it becomes apparent that the defendant’s lawyer is absent from the proceedings. Bewildered by this lack of professional conduct, the Judge turns to a newly-qualified attorney in his mid-20s, who is simply carrying out his military service in the Public Defender’s Office, and instructs him to assume the defendant’s case given that he is already familiar with it. Military service can be completed by undertaking any type of activity linked to the Army and in this case, it involves defending a colonel. The young lawyer was surely not expecting to walk into court that day and have the Colonel’s fate hinge on his shoulders. Nevertheless, he rises to the occasion and starts cross-examining the Prosecutor’s witnesses one by one.

His passion for the job suddenly starts to radiate throughout the courtroom as he continues to unrelentingly assert his case to the dismay and astonishment of the Prosecutor, who looks on as witness after witness begins to retract their previous testimony against the Colonel. While the young attorney is shining on the spot, the original lawyer for the defendant suddenly shows up. Surprisingly, this prompts the Public Defender to request the Judge to reinstate him as counsel for the defence. To the amazement of the newly-qualified attorney who is now successfully spearheading the defence, the Colonel ironically pleads with the Judge to reject the Public Defender’s appeal. Nevertheless, the Judge grants the motion and the tardy lawyer is permitted to resume his duties.

The man who made such an impression on the Colonel and the rest of the courtroom for that matter with his adeptness in successfully defending his client was none other than Jacques El-Hakim. Such courtroom drama is hardly typical to come across but it does say something about the caliber of the man who proved himself on that day to be an ardent lawyer who managed to turn the Prosecutor’s case upside down without the luxury of time to prepare. Such natural ability only served to foreshadow a successful career waiting for the young lawyer in the decades to come.

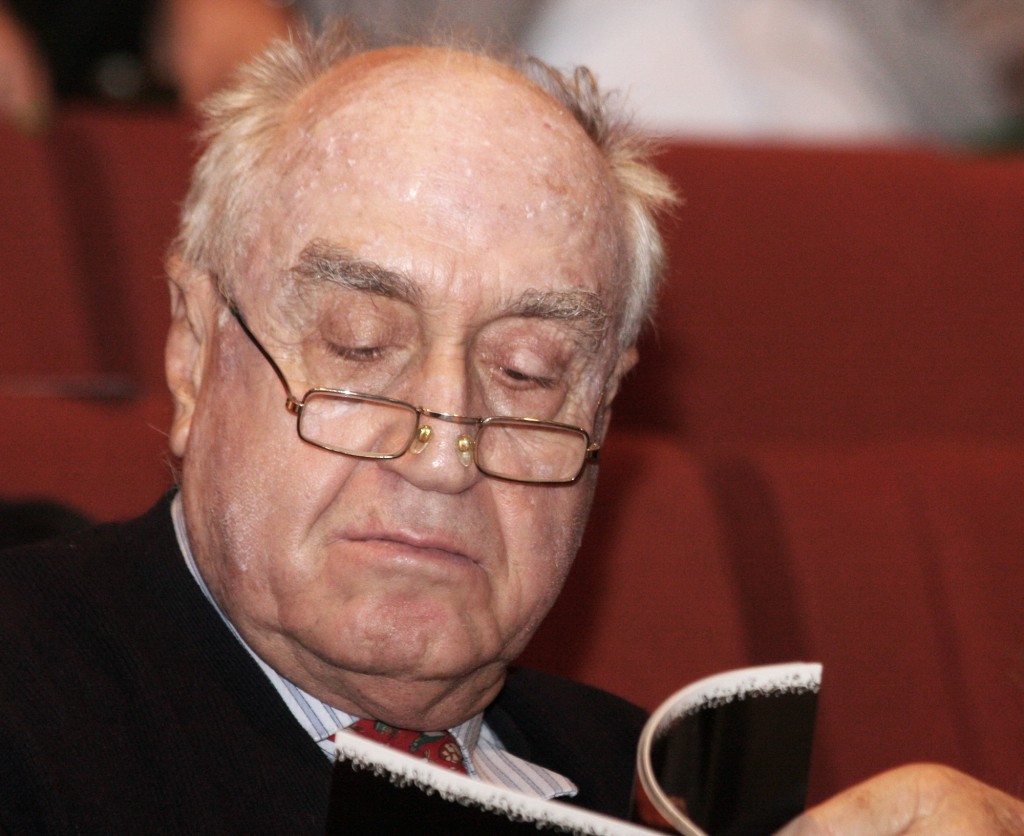

On the occasion of its launch, the Syrian Law Journal (SLJ) sat down with Professor Jacques El-Hakim who is considered by many legal observers as the leading authority on Syrian law, with which his name has become virtually synonymous. Since he has devoted much of his life to his legal career, he has a considerable amount of knowledge to impart when it comes to matters of the law. As part of the discussion, he shared personal details of his lengthy career as a lawyer and law professor, and contributions he has made to the development of the Syrian legal system. Furthermore, he touched on the history of Syrian law and speculated about its future.

Early Years

Before that extraordinary day in court, Jacques El-Hakim’s quest into the legal world began a few years earlier when he set out from Damascus on a journey to Beirut to enroll at the Saint Joseph University. Located on the Monot Street, this renowned institution famed for producing highly-skilled lawyers found itself within close distance of the frontline separating warring factions less than three decades later. Immediately after graduating in 1952 with a degree in Law and Economics, Professor El-Hakim gained his qualification as a trainee lawyer before becoming fully acquainted with Syrian law at the University of Damascus. Even though he was fond of his new adopted city of Beirut, with which he continues to enjoy a strong bond, he remained committed to his native Syria and wished to establish himself back home in Damascus. Syrian law required him to join one bar association only and therefore, he opted to join the Damascus Bar Association after he successfully passed the entrance exam in 1954.

As a certified attorney-at-law in his mid-20s, the young El-Hakim could not but notice the political instability at home, although like many Syrians, he was growing accustomed to it. By this time, he had seen Syria joyfully gain independence from France in 1946 while as a secondary school student and bore witness to a number of coups d’état that had far-reaching ramifications for the country. Nevertheless, he was determined not to allow these events to hinder his ambition of pursuing his calling as a lawyer and professor. He therefore decided to set up his own law firm, which is regarded as one of the most prestigious in Syria until today. Among an abundance of clients over the decades, he has represented several embassies, banks and other companies whose lines of business include insurance, telecommunications, petroleum, aviation and much more. Although he became a law practitioner, his pursuit of an academic career was also within reach.

Despite the not-so-distant tense history with the mandate authority, the French maintained strong academic relations with the Levant that found many admirers among the local population for decades after the independence movements of the 1940s. As part of the earlier generations to pursue a French education, Professor El-Hakim began his Doctorate of Philosophy in Beirut where he was affiliated with the University of Lyon in France. The topic of his thesis was the evaluation of damages under Islamic law and its survival under modern Syrian law. With a Ph.D. to add to his name, he was prepared to undertake a career as a law lecturer. However, he had to participate in an arduous competition known as the agrégation enabling him to teach in any French university after grasping expertise knowledge of French legislation and case law. Having successfully completed it, he is the only Syrian national to do so, which is considered a notable accomplishment.

With a number of distinguished qualifications in his possession, including a diploma in Economics from the University of Colorado, Professor El-Hakim was now ready to impart his knowledge on a new generation of law students. By 1958, he was teaching in both Syria and Lebanon where he lectured on the numerous legal codes- the Civil, Commercial and Criminal Codes, the Maritime Law, and the Labour and Social Security Laws- and the economy. His students were also revising from textbooks that he had personally authored. At the University of Damascus, the governing body recognized his prowess and tasked him with heading up the Commercial Law Department. Meanwhile in Beirut, he became a professor of French law at the Lebanese University educating others on the jurisprudence of a country he had become very well acquainted with by this time in his life. While he was there, the administration set up a special diploma program to prepare law students who aspired to study abroad in Europe and requested Professor El-Hakim to lecture them on the fine points of arbitration. More than five decades later and he is back in the auditorium but this time his audience is comprised of a group of potential Ph.D. students at his alma mater Saint Joseph University and the Lebanese University.

As his professorial career was taking off in the 1950s, Syria was undergoing substantial changes. The 1958 union with Egypt under President Gamal Abdel-Nasser was ushering in socialist legislation in Syria while in Lebanon politicians were trying to keep the populist appeal of the Egyptian leader at bay. Up until that point, Syria and Lebanon were charting similar courses as free market economies moving past the French mandate. This was reflected by the legal systems both countries had adopted and the ease by which Professor El-Hakim was able to teach Syrian law one day and Lebanese law another without much difference in content. As he clarifies, this state of affairs started to change when Syria and Egypt merged to form the United Arab Republic.

Thereupon, Syria began adopting the socialist laws which pushed through nationalizations and land reform that had been visited upon Egypt when Nasser came to power. With Syria shifting away from the path it had previously set on, the Lebanese government led by President Camille Chamoun tried to thwart the pan-Arab leftist appeal brought on by Nasser in the Lebanese street, which began clamouring for unity with Egypt and Syria. As a result, Lebanon went through a brief period of civil strife in 1958, which was a prelude to the 15-year conflict that would follow starting in 1975. As a professor in both countries during this historic time period, Professor El-Hakim believes that the schism created between the Syrian and Lebanese legal systems can be traced back to the policies pursued by Nasser in Syria.

Public Service

While the internal situation in Lebanon descended into all-out war by 1975, Professor El-Hakim began concentrating most of his efforts in Syria. With his private practice and academic career gaining prominence, the notion of public service garnered his interest. Numerous governmental officials over the decades turned to him for his services on several legal projects, similarly as the Judge had done in that courtroom in 1956 when he called on him to defend the Colonel.

For a period of approximately 20 years, the Ministry of Finance requested that he handle major contracts and cases involving the state. By his own admission, this period allowed him to gain further expertise in public transactions and dealings. Despite keeping a busy schedule, he continued in his endeavours to discover new legal fields that would add value to himself, his career and the law.

With his reputation as a reliable legal expert on the rise, Professor El-Hakim was chosen to consult on various commissions in Syria. These were involved in the drafting and amendment of legislation such as those pertaining to commercial and maritime law, the stock market, labour and social security, intellectual property, the media, personal status affairs, criminal law and arbitration. As well as working on international treaties, he drafted legislation to enact the Hamburg Rules governing the international shipment of goods under bills of lading. In this respect, his contributions have had a lasting effect on Syrian law. One noteworthy experience that Professor El-Hakim relays was his appointment by the Minister of Justice to sit on a special commission to consider the drafting of a new commercial code in 1975.

The 1970s in Syria was different from the internal instabilities of the 1960s when divergent factions of the Baath Party competed for power. Socialism in Syria was at its height in the 1960s while the private sector was marginalized to a significant degree. When President Hafez Al-Assad came to power in the early 1970s, he sought to placate the commercial classes by carrying out limited market reforms while maintaining socialism as state policy. With the Commercial Code dating back to 1949, the government of Prime Minister Mahmoud Ayoubi explored the possibility of updating it and called in Professor El-Hakim and other legal experts to participate in the special commission.

The previous Commercial Code combined both general commercial law and company law. At the behest of some members, the commission’s first proposal focused on maintaining the Code in its present form while incorporating certain amendments. Nevertheless, subsequent studies concluded that a separate companies law was a more suitable idea. Therefore, Professor El-Hakim and his colleagues took their queue and began piecing together a collection of provisions to prepare a new commercial code and a companies law.

In fact, the government did not push forward with the passage of the new Commercial Code and the Companies Law until 2007 and 2008 respectively when it began actively pursuing its economic reform program. Professor El-Hakim admits that the original commission set up in 1975 did not take all of his recommendations into account. Since then, the Companies Law underwent another revision in 2011 to reintroduce private joint stock companies among other changes, which were absent from the 2008 law. He notes that while there may be some shortcomings in the legislation, legal reviews in the near future will prove helpful to assess what deficiencies may have resulted from their implementation and what amendments may consequently be recommended.

As can be observed, the legislative process inherent in Syria appears to be protracted in practice and its slow nature is not necessarily something new. Professor El-Hakim reveals that back in the 1950s, the passage of laws proved to be a drawn-out exercise due to the political wrangling between all the diverse political parties in the Parliament. Certain groupings stood against change while progressive factions pressed for reform. There were also occasions when Parliament refused to meet to discuss bills on the agenda for political reasons.

When alluding to the subject of legal reform in the economic sector during the 2000s, Professor El-Hakim admits that the process was actually sped up. Numerous laws were passed during this period with the aim of establishing a social market economy in Syria, which was designed to move away from the socialist policies of the previous 40 years. Regardless, he also clarifies that in a number of cases, it became apparent that these laws omitted important details. To put it another way, while the quantity of legislation increased, the quality did not always meet the required standards. In other instances, lawyers complained of a lack of harmonization between various laws.

While there may be drawbacks in the proper implementation of legislation, Professor El-Hakim believes that to a certain degree, the law is executed according to its text in a number of areas. Once the conflict in Syria draws to a close, he foresees that legislative reform will have to be carried out during the reconstruction period and concurrently, the People’s Assembly (the Parliament) will be expected to exercise its competencies to a fuller extent in doing so.

Personal Initiative

Not long ago, Professor El-Hakim worked on a project to unify all the Christian personal status laws, which had high prospects of success. However, he encountered opposition to this personal initiative, most notably from certain members of the Christian religious establishment who preferred that each denomination maintain its own system of laws. Their stance was reminiscent to a certain degree of the Public Defender’s motion to have Professor El-Hakim replaced during his cross-examinations while he was on a roll.

To put this issue into context, family law in Syria is governed by the Personal Status Law contained in Legislative Decree 59/1953. However, the Druze, Christian and Jewish faiths are permitted to regulate their own marital affairs. Indeed, an important development occurred in 2006 when the Catholic community in Syria was provided with its own consolidated personal status law following the enactment of Law 31/2006, which was separate from the general Personal Status Law. The 2006 law had the effect of reviving the rights of the Catholic denominations prior to the promulgation of the Personal Status Law in 1953 and lending a role to the Roman Rota Court in the Vatican to serve as a final appellate court.

Following the passage of Law 31/2006, Professor El-Hakim received governmental support to push forward with plans to apply this Law to the Orthodox denominations as well with certain adjustments such as bypassing the Roman Rota Court. Moreover, he sought the backing of the relevant religious authorities in this regard. After holding consultations with them, it became evident to him that they were not interested in pursuing this proposal for their own religious reasons. Without their encouragement in sight, Professor El-Hakim found himself unable to move any further on this initiative, which he viewed as a momentous opportunity not worth giving up. As he recalls this episode, the frustration in his voice is difficult to miss.

Not long thereafter, this favourable atmosphere to pursue change would disappear leaving no more chances to push forward on this point in question. Despite the progressive stance shown on this issue, the government decided to limit the scope of Law 31/2006 four years later by virtue of Legislative Decree 76/2010. This latest law revives the full authority of the general Personal Status Law with regards to adoption, guardianship and filiation. Moreover, the Court of Cassation’s role as the highest appellate court was restored. However, jurisdiction over inheritance and wills remains under the authority of the Christian spiritual courts as they are known. Professor El-Hakim confesses that he was disappointed with this move as he regarded Law 31/2006 as an achievement for greater autonomy in personal status affairs.

Historical Significance

In his exchange with the SLJ, Professor El-Hakim provides an interesting account of the historical context of the development of Syrian law. He sheds some light on the contributions made by his father, the late Youssef El-Hakim, who played memorable roles during the 20th century. As he does so, one cannot but notice the pride he exhibits when speaking about his father and the accomplishments he achieved in his life. These included participating in the Syrian National Congress that crowned King Faisal in 1918 alongside the veteran statesman Hashim Atassi, becoming the first President of the Court of Cassation and serving as Minister of Justice. A constant reminder of the El-Hakim family legacy is on display in the Palace of Justice in Damascus where Youssef El-Hakim’s portrait decorates the hall where lawyers walk past, one of whom is usually his namesake grandson who has followed in the family tradition.

Professor El-Hakim discloses that when the Ottoman Empire intervened in the First World War, his father was selected as the head of a commission to translate the Ottoman laws and implement them in Lebanon. When the French mandate was imposed over both Syria and Lebanon in 1920, the new governing authority amended some of the Ottoman laws while keeping others in place. For Lebanon, subsequent legislative reform would not start until 1941, which would serve as a template for Syria in the coming years. As mentioned earlier, Syria and Lebanon had much in common from both a legal and economic perspective during this time period, so it made sense for Syrian legislators to refer to the Lebanese legal system as a model in this regard. With this in mind, it becomes apparent why Professor El-Hakim was able to navigate both the Syrian and Lebanese laws concurrently without much difficulty.

Professor El-Hakim demonstrates why specifically the role of the Lebanese legal system became of valuable interest to Syrian legislators early on after independence. In illustrating his point, he refers to the coup led by the Army Chief-of-Staff General Husni Zaim in 1949 as a decisive moment for Syrian law. According to Professor El-Hakim, General Zaim probably felt that his government would not endure for a long time so he wanted to push forward with legal reform as quickly as possible, which meant looking to mainly neighbouring Lebanon for guidance but also to Egyptian legislation.

The Zaim administration only lasted for a mere 138 days in power but it was responsible for the enactment of the Civil Code, the Commercial Code and the Criminal Code. The drafting of these significant laws was supervised by Assaad Kourani, the Minister of Justice during this brief period. Professor El-Hakim became an expert on these pieces of legislation and lectured about them extensively at the University of Damascus. He further notes that with the exception of the Civil Code and parts of the Personal Status Law of 1953, which are based on their Egyptian counterparts, many of the laws passed in Syria during the post-independence period derived from Lebanese legislation. What is more is that his father, who by this time was 70 years old and rich in legal wisdom, contributed to the drafting of the Criminal Code, which is currently in force more than 60 years later.

Following the establishment of the United Arab Republic in 1958, Egyptian legislation became another source of major influence in Syria since both countries were united during this period. In addition to the nationalization program and land reform implemented from Cairo, Professor El-Hakim recalls that the Council of State and the administrative courts, which handle disputes involving the state, were established in 1959 and modeled on the basis of the Egyptian administrative legal system.

Notwithstanding the emphasis on Lebanese and Egyptian laws, Professor El-Hakim points out that property law in Syria is derived to a certain extent from the Ottomans and the French who reformed part of the law during their mandate. He refers to the establishment of the Land Registry in 1926 as one such example of French influence. Furthermore, he explains that in Syria, title by registration is sufficient to prove property ownership in accordance with the Torrens system. Nevertheless, certain aspects of Syrian property law were reproduced from legislation passed by the Egyptian government.

Conclusion

During the meaningful discussions that the SLJ held with Professor Jacques El-Hakim, it proved effortless to detect the high caliber of this man through the affection he exhibited towards his country, its history and its laws, which was evocative of his ability to undo the Prosecutor’s case in that Damascus courtroom in 1956. He shared stories and made observations that were thoroughly enlightening given that he has witnessed numerous milestones in Syrian law for well over 60 years. For any individual with a fervent interest in Syrian law, they would be well advised to peruse the literary works of Professor El-Hakim as they would find it strenuous to come across other figures with such a passion for the laws of his native Syria as him. For this reason, the SLJ deemed it invaluable to learn from the leading authority himself.